Journey to Achieving Unshakeable Inner Peace : Sankhya Yoga

Here is the gist of what these verses explain. You can find the verses, translations and explanations below this section:

The Path to Achieving Unshakeable Inner Peace Through Ancient Wisdom

We all search for a sanctuary of calm in our daily lives, yet thousands seek the secret of achieving unshakeable inner peace through apps, retreats, and self-help books without lasting success. The ancient wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita offers a clear map for achieving unshakeable inner peace that has worked for millennia. In verses 2.67 through 2.72, Shri Krishna reveals to the trembling warrior Arjuna the exact mechanism that steals our tranquility and how achieving unshakeable inner peace is possible for every seeker.

Understanding Why Achieving Unshakeable Inner Peace Eludes Most People

To succeed in achieving unshakeable inner peace we must first understand how we lose it. Krishna warns that if the mind focuses on even a single wandering sense, the intellect is led astray. Just as strong wind pushes a boat off its predetermined course, one uncontrolled sense can sabotage our entire journey toward achieving unshakeable inner peace.

The real breakthrough in achieving unshakeable inner peace comes from recognizing a profound truth. We often blame external events for our anxiety, but the Gita reveals that the real battle for achieving unshakeable inner peace happens within our own focus and attention. The mind that yields to senses creates a disturbance that makes achieving unshakeable inner peace impossible. Understanding this mechanism revolutionizes the approach to achieving unshakeable inner peace because instead of trying to control the world, we learn to master our own consciousness.

The Ocean Method for Achieving Unshakeable Inner Peace

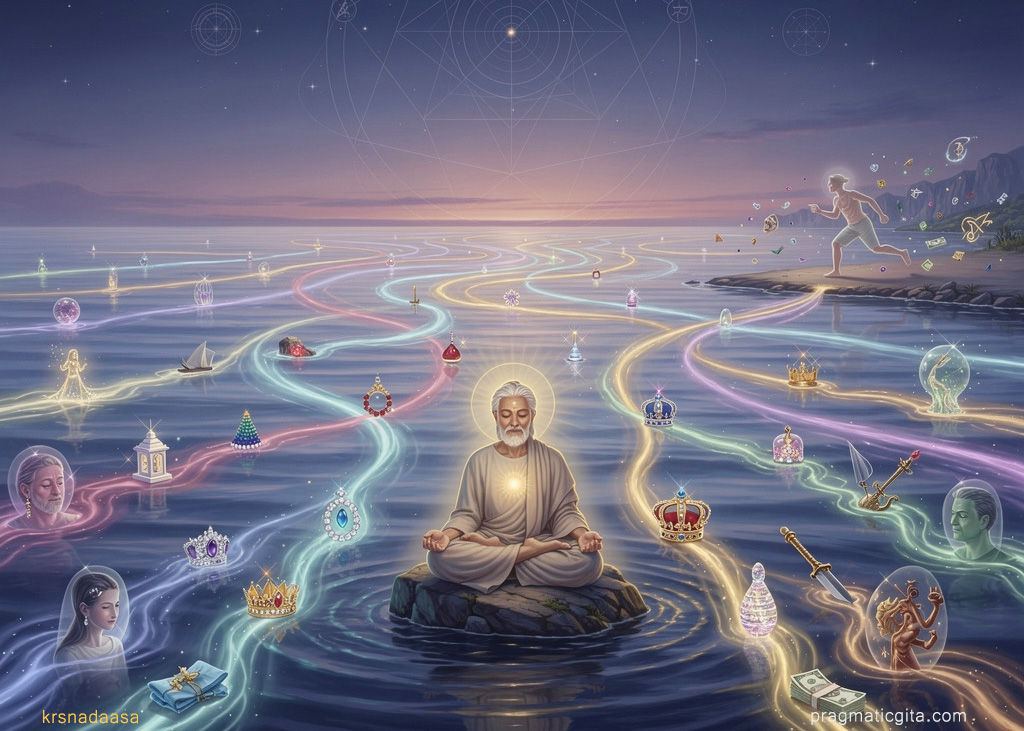

The most powerful image for achieving unshakeable inner peace is the ocean that Krishna presents. Shri Krishna describes the sage as an ocean that is constantly being filled by rivers yet remains steady and unchanging. This metaphor teaches us that achieving unshakeable inner peace does not mean having no desires or distractions. It means developing such profound depth of character where desires can enter without disturbing your essential balance.

This approach to achieving unshakeable inner peace transforms everything. The person who constantly runs behind desires faces perpetual agitation, while the one who watches them flow like rivers into the ocean succeeds in achieving unshakeable inner peace. This ocean-like quality doesn’t require escaping to a monastery. Those succeeding in achieving unshakeable inner peace report that external storms lose their power to create internal chaos because they have developed sufficient inner depth.

The Liberation That Comes With Achieving Unshakeable Inner Peace

The most surprising aspect of achieving unshakeable inner peace involves a complete reversal of values. What society calls success and excitement, those who have succeeded in achieving unshakeable inner peace see as spiritual sleep. Conversely, what appears empty or boring to restless minds becomes the source of deepest fulfillment for those achieving unshakeable inner peace.

Finally, the process of achieving unshakeable inner peace leads to the state known as Brahmi sthiti. This is where one becomes free from the sense of “I” and “mine” and establishes themselves in the Absolute. By letting go of possessiveness and ego, we open the door to achieving unshakeable inner peace permanently. Even at the hour of death, this achieving unshakeable inner peace remains with the sage, leading to ultimate liberation and the end of all delusion.

Your Journey Toward Achieving Unshakeable Inner Peace Begins Now

The journey of achieving unshakeable inner peace follows clear stages anyone can practice. First, recognize how sensory distractions steal your peace moment by moment. Then practice skillful attention management rather than suppression. Develop ocean-like consciousness through patient daily practice. Release ego and possessiveness that create constant agitation. These time-tested steps make achieving unshakeable inner peace not just possible but inevitable.

Whether you struggle with anxiety, seek deeper meaning, or simply want more stability in chaotic times, these teachings on achieving unshakeable inner peace offer both understanding and practical methods. The wisdom for achieving unshakeable inner peace has been preserved for five thousand years because it works. Krishna teaches that achieving unshakeable inner peace is not just a high ideal but a practical state of being that anyone can cultivate by understanding these principles and applying them with dedication.

Keywords: Achieving unshakeable inner peace, Unshakeable Inner Peace, Journey to Inner Stillness, Bhagavad Gita’s path to peace, mastering the mind and senses, cultivating steadfast wisdom, finding calm amidst chaos, overcoming desires and attachments, self-realization through detachment, stages of spiritual awakening, God-consciousness and equanimity, liberating wisdom of the Sthitaprajna, Emotional Equanimity, Brahmi Sthiti, Mastering Consciousness, How to control wandering senses Bhagavad Gita, Gita ocean and rivers metaphor meaning, Overcoming desire and ego, Finding stability in a chaotic world, What is the meaning of Sthitaprajna, How does a sage find peace, Why is the sage awake when others sleep

If you have not already done so, I would request you to review the Chapter 1, Arjuna Vishada Yoga before studying chapter 2 as that would help set the right context.

You can find the explanation of shlokas 61 to 66 here. Please go through that to get better understanding of the context.

You can also listen to all the episodes through my Spotify Portal. And here on YouTube as well.

Verse 2.67 – 2.72

इन्द्रियाणां हि चरतां यन्मनोऽनुविधीयते |

तदस्य हरति प्रज्ञां वायुर्नावमिवाम्भसि || 67||

indriyāṇāṁ hi charatāṁ yan mano ’nuvidhīyate

tadasya harati prajñāṁ vāyur nāvam ivāmbhasi

इन्द्रियाणां (indriyāṇāṁ) – of the senses; हि (hi) – indeed; चरतां (caratāṁ) – moving, wandering; यन्मनोऽनुविधीयते (yanmano’nuvidhīyate) – that which the mind follows; तदस्य (tadasya) – of that; हरति (harati) – takes away; प्रज्ञां (prajñāṁ) – wisdom, intelligence; वायुर् (vāyur) – wind; नावम् (nāvam) – boat; इव (iva) – like; आम्भसि (āmbhasi) – in water;

The mind’s focus on even a single sense can lead the intellect astray, much like how a strong wind can push a boat off its predetermined course on the water.

तस्माद्यस्य महाबाहो निगृहीतानि सर्वश: |

इन्द्रियाणीन्द्रियार्थेभ्यस्तस्य प्रज्ञा प्रतिष्ठिता || 68||

tasmād yasya mahā-bāho nigṛihītāni sarvaśhaḥ

indriyāṇīndriyārthebhyas tasya prajñā pratiṣhṭhitā

तस्माद् (tasmād) – therefore; यस्य (yasya) – whose; महाबाहो (mahābāho) – O mighty-armed one; निगृहीतानि (nigṛhītāni) – controlled, restrained; सर्वश: (sarvaśaḥ) – in all respects; इन्द्रियाणि (indriyāṇi) – senses; इन्द्रियार्थेभ्यः (indriyārthebhyaḥ) – from the objects of senses; तस्य (tasya) – his; प्रज्ञा (prajñā) – wisdom, intelligence; प्रतिष्ठिता (pratiṣṭhitā) – established, steadfast.

Therefore, O mighty-armed one, his or her wisdom is established and steady, whose senses are controlled in all respects, and withdrawn from the objects of senses.

या निशा सर्वभूतानां तस्यां जागर्ति संयमी |

यस्यां जाग्रति भूतानि सा निशा पश्यतो मुने: || 69||

yā niśhā sarva-bhūtānāṁ tasyāṁ jāgarti sanyamī

yasyāṁ jāgrati bhūtāni sā niśhā paśhyato muneḥ

या (yā) – which; निशा (niśā) – night; सर्वभूतानां (sarvabhūtānāṁ) – of all beings; तस्यां (tasyāṁ) – in that; जागर्ति (jāgarti) – is awake; संयमी (saṁyamī) – self-controlled, restrained; यस्यां (yasyāṁ) – in which; जाग्रति (jāgrati) – is awake; भूतानि (bhūtāni) – beings; सा (sā) – that; निशा (niśā) – night; पश्यतो (paśyato) – of the seer; मुने: (muneḥ) – of the sage, ascetic.

That which is night to all beings, in that such a wise person wakes. That in which all beings are awake, is night to the wise sage.

आपूर्यमाणमचलप्रतिष्ठं समुद्रमाप: प्रविशन्ति यद्वत् |

तद्वत्कामा यं प्रविशन्ति सर्वे स शान्तिमाप्नोति न कामकामी || 70||

āpūryamāṇam achala-pratiṣhṭhaṁ samudram āpaḥ praviśhanti yadvat

tadvat kāmā yaṁ praviśhanti sarve sa śhāntim āpnoti na kāma-kāmī

आपूर्यमाणम् (āpūryamāṇam) – constantly filled; अचलप्रतिष्ठं (acalapratiṣṭhaṁ) – unchanging, steady; समुद्रम् (samudram) – ocean; आपः (āpaḥ) – waters; प्रविशन्ति (praviśanti) – enter; यद्वत् (yadvat) – as; तद्वत् (tadvat) – in the same way; कामा (kāmā) – desires; यं (yaṁ) – whom; प्रविशन्ति (praviśanti) – enter; सर्वे (sarve) – all; सः (saḥ) – he; शान्तिम् (śāntim) – peace; आप्नोति (āpnoti) – attains; न (na) – not; कामकामी (kāmakāmī) – one who desires desires.

Just as the ocean remains steady and undisturbed by the constant flow of waters from rivers merging into it, likewise the sage who is unmoved despite the flow of desirable objects all around him attains peace, and not the person who keeps running behind desires.

विहाय कामान्य: सर्वान्पुमांश्चरति नि:स्पृह: |

निर्ममो निरहङ्कार: स शान्तिमधिगच्छति || 71||

vihāya kāmān yaḥ sarvān pumānśh charati niḥspṛihaḥ

nirmamo nirahankāraḥ sa śhāntim adhigachchhati

विहाय (vihāya) – having given up; कामान् (kāmān) – desires; यः (yaḥ) – who; सर्वान् (sarvān) – all; पुमान् (pumān) – a person; चरति (carati) – moves, conducts oneself; निःस्पृहः (niḥspṛhaḥ) – free from longing; निर्ममः (nirmamaḥ) – without possessiveness; निरहङ्कारः (nirahaṅkāraḥ) – without egoism; सः (saḥ) – he; शान्तिम् (śāntim) – peace; अधिगच्छति (adhigacchati) – attains.

That person who is free from sensual longing, free from material desires, and without the sense of proprietorship, and egoism, attains perfect peace.

एषा ब्राह्मी स्थिति: पार्थ नैनां प्राप्य विमुह्यति |

स्थित्वास्यामन्तकालेऽपि ब्रह्मनिर्वाणमृच्छति || 72||

eṣhā brāhmī sthitiḥ pārtha naināṁ prāpya vimuhyati

sthitvāsyām anta-kāle ’pi brahma-nirvāṇam ṛichchhati

एषा (eṣā) – this; ब्राह्मी (brāhmī) – pertaining to Brahman; स्थितिः (sthitiḥ) – state, position; पार्थ (pārtha) – O son of Pritha (Arjuna); न (na) – not; एनाम् (enām) – this; प्राप्य (prāpya) – having attained; विमुह्यति (vimuhyati) – becomes deluded; स्थित्वा (sthitvā) – having established; अस्याम् (asyām) – in this; अन्तकाले (antakāle) – at the end of life; अपि (api) – also; ब्रह्मनिर्वाणम् (brahmanirvāṇam) – absorption in Brahman; ऋच्छति (ṛcchati) – attains.

O Partha, such is the state of a sthitaprajna that having attained it, one is never again deluded. Becoming established in this state, even at the hour of death, one is liberated from the cycle of life and death and reaches the Supreme Abode of God.

Journey to Achieving Unshakeable Inner Peace: Managing the perilous senses

We discussed the Vivekachudamani verse 76 which spoke about the 5 animals kuraṅga mātaṅga pataṅga bṛiṅga mīnā and how they had a weakness for just one sense and that eventually destroyed them. Shri Kṛṣṇa is saying here again that Just as a strong wind can make even a big ship stray from its path, even one of the senses on which the mind focuses can lead the intellect astray and take away whatever little wisdom we may have. So we must strive to progress on our Journey to Inner Stillness through the disciplining of our senses and strengthening of our devotion for God.

And as discussed in the previous verses, the best way to domesticate our senses is by tying them to God consciousness and utilizing them in the service of God, just as maharaja Ambarish demonstrated.

The guru and God can help us understand the importance of controlling our senses and the techniques for doing it. However, they cannot control our senses. Nobody can. Only we can control our senses. To use a good example, if we are hungry, someone can give us food. However, they cannot eat for us. We have to eat our own food and calm our own hunger. Shri Krishna tells Arjuna that He who controls his mind restricts his senses from sense objects. He is fixed in intelligence. O mighty-armed one, just as you control your enemies with your strength, you should also control your mind.

When Warriors Become Seekers

The conches have already sounded. The air over Kurukshetra is thick with dust and the metallic smell of weapons. Flags snap in restless gusts, as if the very wind itself is rehearsing the violence to come. Lines of warriors stand like moving walls, breathing in unison, eyes scanning for familiar faces that should never have become targets.

Between these two armies, each eighteen akshauhinis strong, stands a single chariot. That chariot that became the stage for the most profound spiritual teaching ever given. On it sits Arjuna, the archer who once pleased Lord Shiva himself in combat. Yet now he feels small with doubt and confusion. His legendary bow Gandiva, gifted by Agni, lies across his lap like a piece of dead wood.

Shri Krishna, who has taken that humble role of a charioteer out of love for his friend, has turned to face him. While thousands watch the battlefield, only Shri Krishna watches Arjuna’s mind.

Shri Krishna addresses Arjuna as “Partha”, the name that connects Arjuna to his mother Kunti’s strength, “we have journeyed far in our discourse. I have shown you the immortal nature of the Self, the path of action without attachment, the characteristics of one established in wisdom. But our teaching remains incomplete.”

“What I will tell you now,” Shri Krishna continues, his voice carrying the authority of one who has witnessed the birth and death of countless universes,” is not just philosophy. I will now reveal how consciousness is carried astray, how it is brought back on track, and what it looks like when wisdom becomes unshakeable.”

The Arc of Understanding

By the time we reach these final verses of Chapter 2, Shri Krishna has already diagnosed the hidden mechanism of the collapse of Arjuna’s mind. Earlier, he traced the chain reaction that begins with contemplation on sense objects and ends in complete inner ruin. [dwelling on sense objects leads to attachment, attachment breeds desire, desire thwarted becomes anger, anger clouds judgment, clouded judgment destroys memory, broken memory ruins discrimination, and ruined discrimination leads to total self-destruction].

Now Shri Krishna provides the mechanism for preventing such downfall. These closing verses construct a portrait of the sthitaprajna, the person of steady wisdom. He seals this teaching with the ultimate promise that says “such steadiness is not mere self-improvement but brahmi sthiti, alignment with the Absolute, culminating in brahma nirvana.”

The Wind That Carries Away Our Wisdom

इन्द्रियाणां हि चरतां यन्मनोऽनुविधीयते |

तदस्य हरति प्रज्ञां वायुर्नावमिवाम्भसि || 67||

indriyāṇāṁ hi charatāṁ yan mano ’nuvidhīyate

tadasya harati prajñāṁ vāyur nāvam ivāmbhasi

The mind’s focus on even a single sense can lead the intellect astray, much like how a strong wind can push a boat off its predetermined course on the water.

Shri Krishna reveals something profound here that questions our usual blame game. We love to fault external circumstances: “That person made me angry,” “That advertisement made me crave for something,” “That situation disturbed my peace.” But Shri Krishna points to a more subtle truth. The sense objects themselves are neutral. It is the mind’s “anuvidhiyate,” this beautiful Sanskrit word that captures the motion of running after, following obediently, yielding to, that creates the disturbance and downfall.

Picture a soldier on guard who abandons their post to chase a cute rabbit. The fortress isn’t weakened by the rabbit. It becomes vulnerable because the guard abandoned their post to run behind that rabbit. Similarly, the mind has a sacred duty as our guardian. When it abandons this post to run after sensory attractions, we become defenseless. The word “anuvidhiyate” contains “anu” (after, following) and “vidhiyate” (is led, is guided), painting a picture of voluntary subordination. The mind that should lead chooses instead to follow, reversing the entire hierarchy of consciousness.

The word prajna also deserves our attention. Built from “pra” (forward, excellent) plus the root “jna” (to know), it represents penetrating understanding instead of just superficial knowledge. This is the crown jewel of human consciousness, the faculty that can distinguish eternal from temporary, Self from non-Self. Shri Krishna describes how clarity disappears so gradually we don’t even notice the moment it left.

In our daily lives, this means that losing inner stability is rarely sudden. It is incremental. One indulgence in scrolling becomes a pattern. One moment of gossip becomes a habit. One fantasy becomes an obsession. The mind that was meant to be a master becomes a servant, and the intellect that was meant to discriminate begins to justify.

Yet Shri Krishna’s compassion is hidden inside the warning. He tells Arjuna that the collapse is not mysterious. It has a mechanism. And anything with a mechanism has a method of operation and control.

The Mighty-Armed One’s True Strength

In 2.68 He says, “Therefore, O mighty-armed one (maha-baho), his or her wisdom is established and steady, whose senses are controlled in all respects, and withdrawn from the objects of senses.“

The address “maha-baho” is psychological brilliance. Shri Krishna doesn’t shame Arjuna for trembling and feeling weak. He reminds him of his true potential. You who can bend and string the mighty Gandiva bow that others cannot even lift, must now learn to master the subtle strings of consciousness.

Shri Krishna teaches that this kind of mind control is not about violent suppression but skillful management. Like a master charioteer who knows exactly how much pressure to apply to the reins, neither letting horses run wild nor pulling so hard they are unable to move.

In our daily lives, this means that self-control is not absence of pleasure but refusal to become a puppet of our senses. The modern world sells a story that desire equals identity, that “being yourself” means following every impulse. Shri Krishna teaches that awareness is identity, and desires must be managed using our intellect, and not blindly chased.

The Great Reversal: When Night Becomes Day

Verse 2.69 reveals a startling secret. The awakened and the sleeping literally live in opposite worlds. What feels like bright daylight to one is deep night to the other. Shri Krishna isn’t speaking in metaphors here. He’s describing two completely different ways of experiencing reality.

Consider this. When most people chase pleasures, accumulate possessions, and seek recognition, they feel fully alive and awake. This is their “day.” But the wise see this same pursuit as a kind of sleep, a dream state where people mistake shadows for substance.

Meanwhile, when the wise turn inward to contemplate the eternal Self, ordinary people see only darkness, boredom, emptiness. They cannot fathom why anyone would “waste” precious life sitting still when there’s so much to achieve, acquire, enjoy.

This isn’t about judgment or superiority. It’s about recognizing that spiritual awakening genuinely inverts our entire perception. The saints see light where others see darkness, find fullness where others perceive emptiness.

या निशा सर्वभूतानां तस्यां जागर्ति संयमी |

यस्यां जाग्रति भूतानि सा निशा पश्यतो मुने: || 69||

yā niśhā sarva-bhūtānāṁ tasyāṁ jāgarti sanyamī

yasyāṁ jāgrati bhūtāni sā niśhā paśhyato muneḥ

That which is night to all beings, in that such a wise person wakes. That in which all beings are awake, is night to the wise sage.

This waking state, where most people spend their entire existence, focuses on external objects, achievements, and experiences. Here, success means accumulation, happiness means pleasure, and reality means what we can measure and possess. This is the daylight world of the majority, bright with the glitter of material pursuits.

But the sage has awakened to something else entirely. While others chase shadows on the wall of material existence, the sage has turned to see the light that casts the shadows.

In our daily lives, this means that spiritual life will often appear unreasonable to those whose definition of success is purely external. The person who wakes at 4 AM for meditation appears to be missing the “good life” of sleeping late. The person content with simple living appears to lack ambition. The person who finds joy in service appears to be wasting their talents.

Consider how the two orientations view fundamental life questions:

The worldly person asks, “How can I get more?” The sage asks, “How can I need less?”

The worldly person fears death as the ultimate loss. The sage knows it as a transition within the deathless Self.

The worldly person seeks security in accumulation. The sage finds it in letting go.

The worldly person sees others as competitors for limited resources. The sage sees all as expressions of the same consciousness.

Shri Krishna prepares Arjuna for the temporary loneliness of right perception, the friction that comes when we start living by the right values. Yet he also offers hope. Every human can make the transition from one mode to the other. The Bhagavata Purana tells of Dhruva, a child who began his spiritual journey seeking a kingdom that was far greater than his father’s, but discovered devotion to the Lord, which was something infinitely greater. What starts as material desire can become a doorway to transcendence.

The Ocean That Cannot Overflow

Then, verse 2.70 offers perhaps the most compassionate and practical image in all spiritual literature. The sage is not described as someone with no desires entering the mind. Desires enter their minds too, like rivers that keep flowing. The key is in their capacity to receive without disturbance.

आपूर्यमाणम् अचल प्रतिष्ठं समुद्रम् आप: प्रविशन्ति यद्वत् |

तद्वत् कामा: यं प्रविशन्ति सर्वे स: शान्तिम् आप्नोति न काम कामी || 70||

āpūryamāṇam achala-pratiṣhṭhaṁ samudram āpaḥ praviśhanti yadvat

tadvat kāmā yaṁ praviśhanti sarve sa śhāntim āpnoti na kāma-kāmī

Just as the ocean remains steady and undisturbed by the constant flow of waters from rivers merging into it, likewise the sage who is unmoved by the flow of desires entering him attains peace, and not the person who keeps running behind desires.

The ocean metaphor corrects a dangerous misunderstanding. Spiritual maturity does not require a sterile place where no distractions exist. It requires us to become like an ocean deep enough that no distractions can disturb it.

The phrase “achala-pratishtham” (unshakably established) paired with “apuryamanam” (continuously being filled) presents the paradox of dynamic reception with constant stability.

In our daily lives, this means that peace is not dependent on removing every trigger. Peace depends on deepening our inner container. If the mind is a shallow puddle, every small disturbance will cause the water to overflow. If the mind is a deep ocean, the same disturbance creates only surface ripples while the depths remain serene.

The crucial term “kama-kami” (desirer of desires) points to those who are constantly running behind desires. Such people can never experience true happiness or peace.

Beyond the Prison of Identity

In 2.71, Shri Krishna identifies the specific mental conditions that either cultivate or prevent ocean-like consciousness. The three terms he uses, nihspriha (without craving), nirmama (without mine-ness), and nirahankara (without ego), form a complete diagnosis of human bondage and its cure.

“Spriha” is not just desire but the thirsty, restless reaching that keeps consciousness agitated. It’s the mental state of the person who can never fully enjoy the present because they’re already planning the next acquisition. “Nihspriha” means being free from this desperate thirst and restlessness.

“Mama” (mine) represents our attempt to create security through possession. From childhood’s “my toy” to adulthood’s “my house, my career, my reputation, my family,” we build elaborate structures of ownership. Yet everything we call “mine” exists only temporarily under our control. The house breaks, the career ends, loved ones leave, etc. The tighter we grasp, the more we suffer when life’s inevitable changes occur.

“Ahankara” literally means “I-making,” the continuous construction of a separate self that must be defended, promoted, and satisfied. It’s the story-telling function that converts raw experience into personal narrative: “I am the one who succeeded,” “I am the one who was wronged,” “I am the one who deserves better.”

In our daily lives, this means that much of our suffering does not come from events themselves but from the ownership patterns we impose on them. A setback at work becomes suffering when filtered through “my career.” A relationship challenge becomes agony when processed through “my happiness depends on this.” Even positive experiences become sources of anxiety when claimed as “my achievement” that must be protected and repeated.

The sage Nisargadatta Maharaj pointed to this with laser clarity: “The real world is beyond the mind’s ken; we see it through the net of our desires, divided into pleasure and pain, right and wrong, inner and outer. To see the universe as it is, you must step beyond the net. It is not hard to do so, for the net is full of holes.”

These holes appear in moments of self-forgetfulness like being absorbed in creative work, dissolved in love, lost in beauty, immersed in service. In these moments, “I” and “mine” temporarily vanish, and we taste our true nature. The sage has made this their permanent state.

The Summit: Living Liberation

एषा ब्राह्मी स्थिति: पार्थ नैनां प्राप्य विमुह्यति |

स्थित्वास्यामन्तकालेऽपि ब्रह्मनिर्वाणमृच्छति || 72||

eṣhā brāhmī sthitiḥ pārtha naināṁ prāpya vimuhyati

sthitvāsyām anta-kāle ’pi brahma-nirvāṇam ṛichchhati

O Partha, such is the state of a sthitaprajna that having attained it, one is never again deluded. Becoming established in this state, even at the hour of death, one is liberated from the cycle of life and death and reaches the Supreme Abode of God.

With these words, Shri Krishna places the capstone on Chapter 2’s architecture of wisdom. The term “brahmi sthiti” represents the culmination of human potential as our recovered original nature instead of as a distant achievement.

“Brahmi” means “of Brahman,” pertaining to the absolute reality that underlies all existence. “Sthiti” means state, position, or establishment. This is not a temporary experience or altered state but a fundamental shift in the locus of identity from the changing to the changeless.

Shri Krishna emphasizes three crucial aspects:

Irreversibility: “nainam prapya vimuhyati” (having attained this, one is never again deluded). This isn’t like worldly achievements that can be lost. Once you truly know you are the ocean, you can never again believe you are merely a single wave. The recognition is self-validating and self-sustaining because it is a recollection of what was always true, not an acquisition of something foreign.

Stability even in transition: “anta-kale ‘pi” (even at the hour of death). Death represents the ultimate test of realization. All external supports fall away. The body fails, relationships end, possessions become meaningless, social identity dissolves. Only what is real within us remains. The established sage faces this transition with the same equanimity they brought to life because they have already died to the false and live in the true.

Complete liberation: “brahma-nirvanam” combines two profound terms. “Brahman” is the absolute reality beyond all categories and limitations. “Nirvana” means extinguishing, but not of existence itself. What is extinguished is the false sense of separation, like a wave recognizing it was always ocean. The individual consciousness doesn’t disappear but realizes its true magnitude.

The Mundaka Upanishad describes this state: (Mundaka 2.2.8)

भिद्यते हृदयग्रन्थिश्छिद्यन्ते सर्वसंशयाः ।

क्षीयन्ते चास्य कर्माणि तस्मिन्दृष्टे परावरे ॥ ८ ॥

bhidyate hridayagranthish chhidyante sarvasamshayah

kshiyante chasya karmani tasmindrishte paravare

The knot of the heart is broken, all doubts are resolved, and all karmas are exhausted when one realizes that Supreme which is both high and low.

This promise transforms how we view the spiritual path. It’s not about adding something we lack but uncovering what we always were.

In our daily lives, this means that every moment of practice contributes to an inevitable revelation. The ocean was always there; we’re simply removing the mental barriers that made us feel like isolated drops or waves. Each time we don’t follow a sensory pull, each time we receive experience without disturbance, each time we act without “I” and “mine,” we weaken the illusion of separation.

The practical path follows the progression Shri Krishna has outlined:

First, we recognize our predicament through honest self-observation. We see how sensory winds blow our mental ship off course. We notice the moment when scrolling steals an hour, when imagination creates unnecessary drama, when comparison generates suffering. Etc.

Then we develop discipline through small, consistent actions. Not harsh suppression but skillful management of attention. We pre-decide our responses to predictable triggers. We design our environment to support our highest aspirations. We treat our senses like powerful horses that need proper training, not enemies to be destroyed.

We begin experiencing the reversal of values as our practice deepens. What once seemed exciting now appears empty. What once seemed boring now feels exciting. We find more joy in stillness than in stimulation. The opinions of those living in “darkness” matter less as we taste the light of awareness.

We cultivate ocean-like consciousness through patient practice. We start with small disturbances, practicing non-reactivity to minor irritations. Gradually we build capacity for larger waves. We discover that the ocean of consciousness has infinite depth and nothing can cause it to overflow.

We practice releasing “I” and “mine” in daily experiments. We give credit generously, hold possessions lightly, accept feedback gracefully. We notice how each release creates more space, more freedom, more joy. What we feared would be loss reveals itself as liberation.

Finally, through grace and practice combined, we become established in our true nature. The brahmi sthiti that seemed impossibly distant becomes our lived reality. We act in the world while resting in the eternal. We play our roles while knowing our true identity. We face even death as simply another experience arising in the deathless awareness we have recognized as our Self.

The Call That Echoes Through Time

As we complete this exploration of Sankhya Yoga’s final verses, we return to that dawn battlefield where it began. The external scene remains unchanged: two armies, inevitable conflict, difficult choices. Yet everything has transformed because consciousness has transformed.

Arjuna began paralyzed by confusion, his discrimination blown about like a ship in a storm. Through Shri Krishna’s teaching, he discovers the possibility of unshakeable stability, ocean-like consciousness that receives all experience without disturbance, freedom beyond “I” and “mine,” and ultimately, the divine state that transcends even death.

This transformation awaits every sincere seeker. The battlefield of Kurukshetra symbolizes our daily life where we face constant choices between wisdom and ignorance, between what elevates and what binds. Shri Krishna’s teachings stand as eternal guidance, speaking directly to our present challenges while pointing to timeless truths.

We live in times of unprecedented sensory assault. The forces trying to steal our prajna have multiplied exponentially. Apps are designed by neuroscientists to maximize addiction. News cycles trigger ancient fear responses. Social media converts the need for connection into competitive display. The winds threatening to blow our boat off course have become hurricanes.

Yet these same challenges can accelerate our growth. The intensity of modern life makes the need for inner stability more urgent. We have access to the best of humanity’s spiritual heritage at our fingertips. The question is whether we use this access for liberation or further bondage.

How to remain steady like the ocean

We may ask the question, how exactly can we remain steady like the ocean when desires flow like rivers into our mind? This is the same question that King Yadu asked a wandering monk. This story is described in the Srimad Bhagavatam. King Yadu was an ancient Indian ruler and was the son of King Yayati and Queen Devayani. He was the founder of the Yadava dynasty. Lord Krishna was born in this dynasty.

King Yadu once came across a young and very handsome wandering sage, who looked very calm and peaceful. He immediately realizes that this is an elevated soul and he bows down to this sage and asks him with a lot of humility “O great sage, can you please tell me the secret of the peace and serenity that you seem to be constantly experiencing, in spite of all the material disturbances all around you?”.

Pleased by his humility, the sage responds: “O King, I have taken shelter of twenty-four gurus, who are the following: the earth, air, sky, water, fire, moon, sun, pigeon and python; the sea, moth, honeybee, elephant and honey thief; the deer, the fish, the prostitute Piṅgalā, the kurara bird and the child; and the young girl, arrow maker, serpent, spider and wasp. My dear King, by studying their activities I have learned the science of the self.”

I will try to explain a few of these lessons in simple terms. A few lessons we have already learned in previous shlokas of this chapter.

A sober person, even when harassed by other living beings, should understand that his aggressors are acting helplessly under the control of their gunas, and thus we should never be distracted from progress on our own path. This rule I have learned from the earth.

A saintly person can carry various material objects, however, never get entangled in those objects, just like the wind.

A wise person should know that they are a pure spirit soul, even when living in a physical body. Both individual souls and the Supersoul are like the sky: they are everywhere, but they don’t mix with anything and can’t be divided by anything.

O King, a saintly person is like water. Pure, gentle, and creates pleasing sounds when speaking. When someone sees, touches, or hears them, they become purified, like being cleansed by clean water. Such a person stays pure by constantly chanting the Lord’s name.

A saintly person should be like the fire, which never gets contaminated by anything thrown at it, but rather burns away all contamination.

Time causes various changes to the body but this does not affect the soul, just as the apparent waxing and waning of the moon does not affect the moon itself.

Just as the sun evaporates large quantities of water by its potent rays and later returns the water to the earth in the form of rain, a saintly person is not impacted when they accept any material offerings nor disturbed when they give it away to other people.

If at any time food is not available, then a saintly person should fast for many days without feeling anxious. They should understand that by God’s arrangement they must fast. Thus, following the example of the python, they should remain peaceful and patient.

Just as the honey bee takes nectar from all flowers, big and small, an intelligent human being should take the essence from all scriptural teachings.

Egiye Jao

Sri Ramakrishna shared a profound parable that teaches the importance of progressing and moving forward. In Bengali, “egiye jāo” means “march onward” or “move forward”. The story revolves around a woodcutter who made a living by cutting a small amount of wood from the outskirts of the forest and selling it in the market. He continued doing this for many years until one day, a holy man walked by and advised him “egiye jāo.”

Initially, the woodcutter did not understand the holy man’s advice and wondered why he should move forward when there was so much wood available right where he was. However, eventually, he decided to heed his advice and go deeper into the forest. As he ventured deeper, he discovered higher quality wood, which in turn fetched him more money. Encouraged by this newfound success, the woodcutter decided to venture even deeper into the forest.

He then discovered a copper mine, and made more money. Ventured deeper into the forest and discovered a gold mine, and ultimately, a diamond mine. Through this journey, the woodcutter became incredibly wealthy. Sri Ramakrishna used this parable of “egiye jāo” to emphasize that spiritual life is also a journey of continuous progress.

As we embark on our spiritual journey, we must strive to move forward and embrace greater spiritual experiences that await us. Just like the woodcutter in the parable, we should never be content with where we are and must always be willing to venture deeper into our spiritual journey.

Maybe today we can’t even get up early in the morning so we first practice that. Then we practice thinking of God the first thing in the morning. And then we practice feeling grateful for what we have and thanking God. Then we practice chanting God’s name. Listening to God’s stories and teachings. Then we venture deeper and try practicing the teachings. And so on and so forth, until we reach the stage of self-realization and God-realization.

The path doesn’t demand perfection but persistence.

Like a river that eventually reaches the ocean through patient flow, not violent rushing, we progress through daily practice. Some days the river runs strong, others it barely trickles, but it never stops moving toward its destination.

Remember that reading about water doesn’t quench thirst. Studying maps doesn’t equal experiencing the journey. These teachings come alive only through practice, through the willingness to begin where we are and take one step, then another, with faith that each sincere effort brings us closer to the peace that is our birthright.

May Shri Krishna’s promise inspire us across whatever distances of time and space separate us from that battlefield: This divine state exists. It can be attained. Once established, it transcends all change, all loss, even death itself.

The teaching is complete. The path is clear. The destination is inviting us. All that remains is to take the first step, then the next, with the confidence that we walk a path countless others have walked before us, leading to the same eternal destination.

The external battle at Kurukshetra would rage for eighteen days. But the internal battle was won in this moment of teaching, when confusion gave way to clarity, when paralysis transformed into purposeful action, when a warrior discovered the sage within himself. That same discovery awaits each of us, not on some distant battlefield but in the midst of our daily lives, whenever we choose awareness over automaticity, whenever we choose the eternal over the ephemeral, whenever we remember who we truly are.

“ॐ तत्सत्” – “Om Tat Sat” – Thus Truth is declared.

Thus concludes the teaching on the Yoga of Knowledge, the second chapter of the blessed Bhagavad Gita, the dialogue between Shri Krishna and Arjuna in the midst of life’s battlefield.

You can go through Chapter 3, Karma Yoga, starting here:

kṛṣṇadaasa

Servant of Krishna