Journey From Jnana to Dharma to Karma: Karma Yoga

Here is the gist of what these verses explain. You can find the verses, translations and detailed explanations below this section:

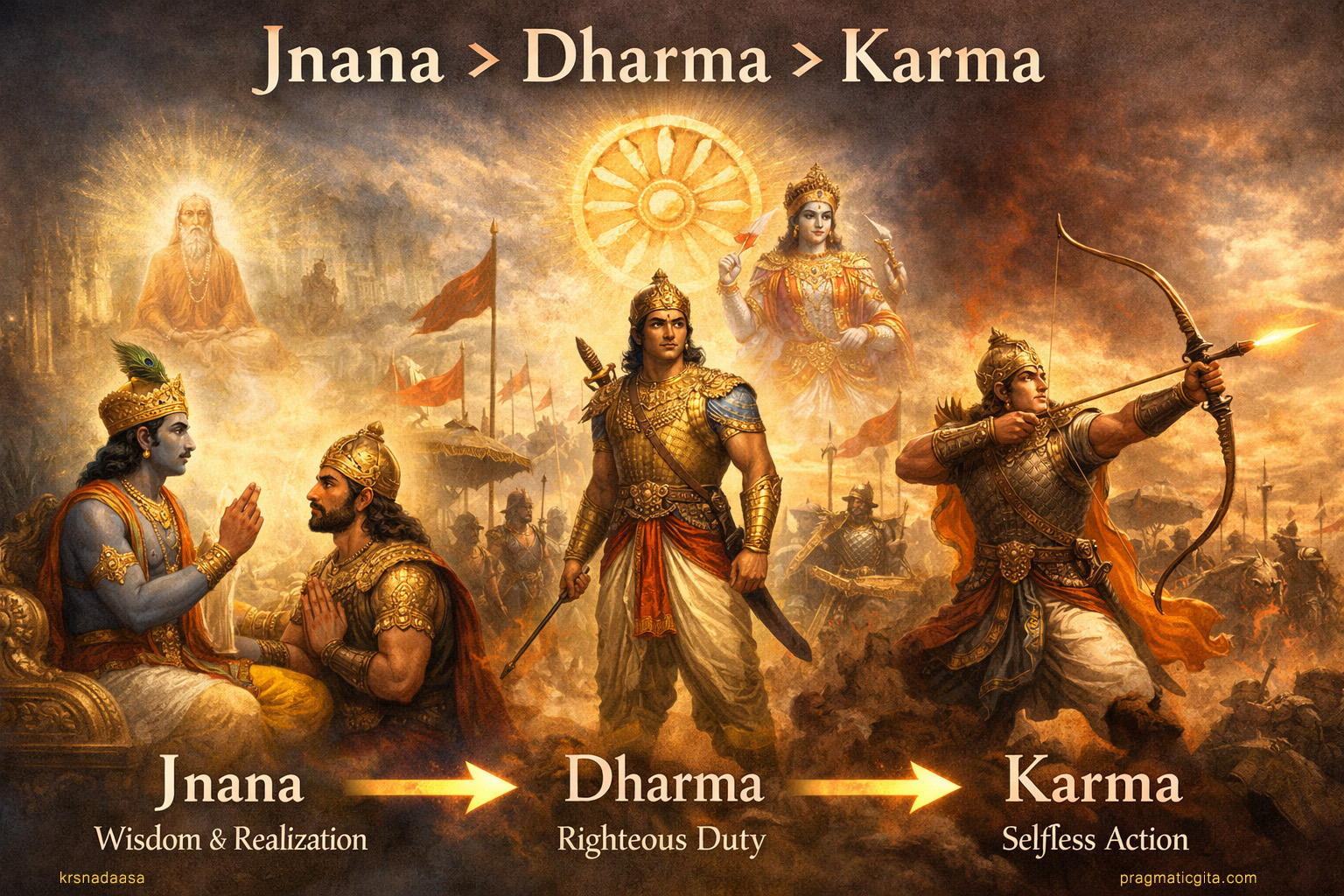

The third chapter of the Bhagavad Gita opens with one of the most psychologically honest moments in spiritual literature. Arjuna, having received the soaring vision of Chapter 2, now stands with a question that burns. If Sankhya, the path of knowledge, reveals the eternal Atman beyond all change, and if Buddhi Yoga leads to steady wisdom, then why this insistence on terrible action? The Bhagavad Gita 3.1 3.2 meaning unfolds from this very tension, revealing the journey from jnana to dharma to karma that every sincere seeker must walk.

Arjuna’s Confusion in Chapter 3: The Honest Question

In verses 3.1 and 3.2, Arjuna speaks with striking candor. He uses the phrase vyamishreneva vakyena, telling Krishna that his words seem mixed or contradictory. The meaning of vyamishreneva vakyena points to genuine bewilderment rather than complaint. Arjuna has heard Krishna praise the stillness of the sthita prajna. He has absorbed the teaching that weapons cannot cut the Self and fire cannot burn it. And yet Krishna urges him toward war.

Why does Krishna urge Arjuna to fight after delivering such transcendent teaching? This question is not Arjuna being difficult. It is the natural result of deeply hearing a teaching and then facing the demands of embodied life. Arjuna asks for the path to Shreyas or Ultimate Good, wanting clarity about which direction leads to liberation.

From Deha Buddhi to Atma Buddhi: The Inner Shift

Chapter 2 established the fundamental error that underlies all confusion. Arjuna had been operating from Deha Buddhi, identification with the body, which made the battlefield appear as a site of irreversible destruction. Krishna’s teaching aimed to shift him toward Atma Buddhi, identification with the Self that cannot be destroyed.

But intellectual understanding is not the same as lived realization. Arjuna grasped the teaching of Sankhya. He understood that the Atman is nitya, eternal, and avinashi, indestructible. Yet understanding alone does not dissolve the pull of duty and the weight of circumstance. The movement from Deha Buddhi to Atma Buddhi requires more than hearing. It requires integration through action.

This is precisely why Krishna emphasizes action after knowledge. Buddhi Yoga, the yoga of intellect, is not meant to remain abstract. It must flow into Nishkama Karma, desireless action, where the insights of discrimination become the foundation for transformed engagement with the world.

Is Renunciation Better Than Action?

Arjuna’s question carries a subtle hope. Having heard Krishna describe the peace of the wise, part of him wonders whether he can simply renounce the battlefield and retreat into contemplation. Is renunciation better than action? This is the question that many seekers ask when spiritual teachings seem to point toward withdrawal.

Krishna will address this directly as Chapter 3 unfolds. The answer is nuanced but clear. True renunciation is not the abandonment of action but the abandonment of craving. The one who acts without attachment, who performs duty as offering rather than transaction, is the true renunciate even while fully engaged. Learning how to practice nishkama karma daily becomes the practical key that unlocks this teaching.

The confusion Arjuna experiences is described in Chapter 2 as dharma sammudha chetah, a mind bewildered about duty. How to overcome dharma sammudha chetah is the very purpose of Chapter 3. The answer lies not in choosing between knowledge and action but in understanding how they unite.

How Do Jnana, Dharma, and Karma Fit Together?

The from jnana to dharma to karma meaning points to an organic progression rather than separate compartments. Jnana is the clear seeing that distinguishes the eternal from the passing. Dharma is the recognition of what is ours to do given our nature and circumstances. Karma is the actual doing, the engagement with life that can bind or liberate depending on the inner orientation.

Why does Krishna tell Arjuna to act after teaching knowledge? Because knowledge that remains only in the head has not completed its journey. It must descend into the hands and feet. It must inform how we meet our obligations, relationships, and choices. The path to Shreyas or Ultimate Good runs through the integration of seeing and doing.

What is the meaning of Gita 3.1 and 3.2? These verses are the hinge between vision and practice. They honor the genuine confusion of a sincere student while setting the stage for the teaching that will resolve it. Chapter 3 exists because Arjuna had the honesty to ask what many seekers feel but hesitate to voice. And in that asking, the deeper teaching of Karma Yoga becomes possible.

If you have not already done so, I would request you to review the Chapter 2, Sankya Yoga before studying chapter 3 as that would help set the right context.

You can also listen to all the episodes through my Spotify Portal. And here on YouTube as well.

Keywords: from jnana to dharma to karma, Sankhya (Path of Knowledge), Buddhi Yoga (Yoga of Intellect), Nishkama Karma (Desireless Action), Arjuna’s confusion in Chapter 3, meaning of vyamishreneva vakyena, path to Shreyas or Ultimate Good, from Deha Buddhi to Atma Buddhi, from jnana to dharma to karma meaning, Bhagavad Gita 3.1 3.2 meaning, why Krishna emphasizes action after knowledge, how to practice nishkama karma daily, Why does Krishna urge Arjuna to fight?, Is renunciation better than action?, How to overcome dharma sammudha chetah, Why does Krishna tell Arjuna to act after teaching knowledge?, What is the meaning of Gita 3.1 and 3.2?, How do jnana, dharma, and karma fit together?

Chapter 3 – Karma Yoga

Recap of Chapter 2 From Deha Buddhi to Atma Buddhi

Something breaks in Arjuna. Not his body, not his weapons, but something deeper. He sits between two vast armies, surrounded by the sound of conches and war drums, and he cannot move. His bow, the legendary Gandiva, slips from his hands. His skin burns. His mind spins. He tells Shri Krishna that he sees no good in killing his own people. He would rather be killed himself, unarmed and unresisting, than fight this war.

This is not cowardice. Arjuna has fought countless battles. This is something else entirely. This is what happens when a person’s inner framework collapses. The beliefs and assumptions that once made sense no longer hold. The roles that once felt natural now feel unbearable. Arjuna does not know who he is anymore, or what he should do.

He says to Shri Krishna:

कार्पण्य दोषोपहत स्वभाव:

पृच्छामि त्वां धर्मसम्मूढचेता: |

यच्छ्रेय: स्यान्निश्चितं ब्रूहि तन्मे

शिष्यस्तेऽहं शाधि मां त्वां प्रपन्नम् || 7||

kārpaṇya-doṣhopahata-svabhāvaḥ

pṛichchhāmi tvāṁ dharma-sammūḍha-chetāḥ

yach-chhreyaḥ syānniśhchitaṁ brūhi tanme

śhiṣhyaste ’haṁ śhādhi māṁ tvāṁ prapannam

My mind is confused about my duty and I am consumed by anxiety and doubt. I am Your devoted student, and have fully surrendered to You. Please enlighten me on the most appropriate path for me to take.

This is the turning point. Not when Shri Krishna begins to teach, but when Arjuna becomes ready to learn. Until now, Arjuna has been arguing, justifying, explaining his confusion. Now he stops. He admits he does not know. He asks for help.

Many of us will recognize this moment. We may not be on a battlefield, but we have stood at places where the old certainties failed. The most common shock most of us feel in our lives is about relationships. We assume or trust that someone will always be there for us and will always care for us but then that relationship we trusted so much just dissolves. A career we built with so much passion just crumbles. A belief that we held so dearly turns out to be false….

And in that shattering, if we are fortunate, something opens. The Mundaka Upanishad says that the seeker must approach the teacher with fuel in hand, meaning with humility and genuine need. Arjuna has arrived at that point. His crisis has enabled him to approach his teacher, Shri Krishna with such a mindset.

Adi Shankara, commenting on this verse, notes that this moment of prapatti, complete surrender, is what makes the entire Gita possible. Without the student’s readiness, even the greatest teacher, imparting the greatest teaching, cannot make an impact. The ground must be fertile before the seed can grow.

The Root Problem: Deha Buddhi

Shri Krishna’s first response sounded surprising. He does not offer comfort. He does not simply sympathise or console Arjuna. Instead, he says something that sounds almost harsh:

श्रीभगवान् उवाच ।

अशोच्यान् अन्वशोचः त्वं प्रज्ञा-वदान् च भाषसे ।

गत-असून् अगत-असून् च न अनुशोचन्ति पण्डिताः ॥ ११ ॥

śrī bhagavān uvāca

aśocyān anvaśocas tvaṁ prajñā-vādāṁś ca bhāṣase

gatāsūn agatāsūṁś ca nānuśocanti paṇḍitāḥ

The Supreme Lord said: While you speak words of wisdom like a Pandita, you are mourning for that which is not worthy of grief. The wise lament neither for the living nor for the dead.

What does this mean? Arjuna has just given eloquent reasons for not fighting. He has spoken about dharma, about the destruction of families, about the sin of killing teachers and elders. These sound like wise concerns. Why does Shri Krishna brush them aside?

Because Arjuna’s reasoning, however sophisticated, is built on a false foundation. He is operating from deha buddhi, the deep-seated habit of taking ourselves to be the body. From this assumption, everything else follows. If my grandfather Bhishma is his body, then killing that body means destroying Bhishma. If my teacher Drona is his body, then his death is the end of Drona. From deha buddhi, the battlefield becomes a site of irreversible destruction, and Arjuna’s grief makes complete sense.

But what if the assumption is wrong?

This is where Shri Krishna begins. Not with ethics or strategy, but with the most fundamental question there is: Who are we, really?

The Atman: That Which Cannot Be Destroyed

Shri Krishna is pointing to something very fundamental. Behind every body, behind every personality, behind every role and name, there is sat, pure existence, pure being, that which simply is. This is the ātman. It does not come into being at birth, and it does not go out of being at death. It is nitya, eternal. It is avināśī, indestructible. It is aja, unborn.

Shri Krishna draws directly from the Katha Upanishad 1.2.18, where Yama teaches the young Nachiketa:

न जायते म्रियते वा विपश्चित्

नायं कुतश्चिन्न बभूव कश्चित् ।

अजो नित्यः शाश्वतोऽयं पुराणो

न हन्यते हन्यमाने शरीरे ॥

na jāyate mriyate vā vipaścit

nāyaṁ kutaścin na babhūva kaścit

ajo nityaḥ śāśvato ‘yaṁ purāṇo

na hanyate hanyamāne śarīre

The knowing Self is not born, nor does it die. It did not originate from anything, nor did anything originate from it. Unborn, eternal, undecaying, ancient, it is not killed when the body is killed.

Shri Krishna echoes this teaching almost word for word. He wants Arjuna to understand that what he fears destroying cannot be destroyed. Nainaṁ chindanti śastrāṇi, nainaṁ dahati pāvakaḥ, “Weapons do not cut it, fire does not burn it.”

Anything that can be cut or burned belongs to the realm of matter, of prakṛti, of the ever changing. The ātman is not in that category. It is the awareness in which all experience appears, the witness of all change, itself never changing.

Shri Krishna offers a simple image:

तथा शरीराणि विहाय जीर्णा

न्यन्यानि संयाति नवानि देही || 22||

vāsānsi jīrṇāni yathā vihāya

navāni gṛihṇāti naro ’parāṇi

tathā śharīrāṇi vihāya jīrṇānya

nyāni sanyāti navāni dehī

As a person sheds worn-out garments and wears new ones, likewise, at the time of death, the soul casts off its worn-out body and enters a new one.

The body is like a garment. It is worn for a time. It serves its purpose. Then it is discarded. The garment is destroyed, but the one who wears it remains.

This teaching is not meant to make us indifferent to life or to the body. It is meant to correct a deep error in perception. When we mistake the garment for the wearer, we live in constant fear of loss. When we see clearly, that fear loosens. We still care for the body, just as we care for our clothes. But we are no longer confused about what we are.

Swami Chinmayananda, in his commentary on these verses, points out that this is not a belief to be accepted on faith. It is an investigation to be undertaken. “Who am I?” is the fundamental question of Vedanta. Shri Krishna is inviting Arjuna, and through Arjuna all of us, to look past the apparent, past the body and the thoughts and the emotions, and discover what remains when all of that is set aside.

Svadharma, The Call of Our Own Nature

Having established the indestructibility of the Self, Shri Krishna turns to the question of action. If Arjuna is not the body, if no one is truly killed, does that mean nothing matters? Can we do whatever we want?

No. Shri Krishna introduces svadharma, the law of our own being, and our prescribed duties.

Arjuna is a kṣatriya. This is not merely a social category or an accident of birth. It indicates a certain svabhāva, a certain inner nature. Arjuna’s inner nature is that of a protector. He has the capacity for decisive action, for leadership, for standing firm when dharma is threatened. This capacity is not random. It is what he has taken birth to express.

Shri Krishna says: As a warrior, it’s your duty to stay steadfast and unwavering. In fact, there’s no greater calling for a warrior than to fight for the sake of righteousness (dharma).

And, understanding that Arjuna’s deepest fear is not death but spiritual failure, Shri Krishna offers extraordinary comfort through verse 2.40:

nehābhikrama-nāśho ’sti pratyavāyo na vidyate – On this path of awakened action, there is no loss of effort, no harmful consequence.

svalpam apyasya dharmasya trāyate mahato bhayāt – Even a little practice of this dharma protects from great fear.

No sincere spiritual effort is wasted, for any step toward truth leaves a permanent mark on one’s mind.

Arjuna’s wish to renounce the battle and live as a mendicant might appear spiritual. But it would be para-dharma for him, another’s path, not his own. Shri Krishna sees through this. He knows that Arjuna’s talk of renunciation is not coming from genuine vairāgya, dispassion born of clarity, but from moha, confusion, and bhaya, fear dressed up as wisdom. True renunciation is something else entirely. It cannot be chosen as an escape.

Karma Yoga: The Transformation of Action

Then He gave us one of the most important teachings in the Gita, the teaching of karma and niṣkāma karma, rightful action and selfless action without craving for results.

कर्मण्येवाधिकारस्ते मा फलेषु कदाचन |

मा कर्मफलहेतुर्भूर्मा ते सङ्गोऽस्त्वकर्मणि || 2.47 ||

karmaṇy-evādhikāras te mā phaleṣhu kadāchana

mā karma-phala-hetur bhūr mā te saṅgo ’stvakarmaṇi

You have the right to perform your prescribed duties, but you are not entitled to the results of your actions. Never consider yourself the cause of the results of your activities, nor be attached to inaction.

This verse is so often quoted that its revolutionary nature can be missed. Shri Krishna is describing a complete reorientation of how we act. Most of us act from desire. We want something, whether success, recognition, money, pleasure, or approval, and we act in order to get it. The action is a means to an end. If the expected outcome does not come, the action feels wasted. If the expected outcome does come, the action feels lacking as soon our expectations increase and we want something more.

This is what keeps us on the wheel of saṁsāra, endless actions and reactions, endless craving, endless dissatisfaction. We are never fully here, in the action itself. We are always leaning forward into an imagined future, hoping for fruits that may or may not come.

And this leads to a particular kind of suffering that many of us know intimately. We work hard. We act with good intentions. We try to do the right thing. And then we look around and see others who seem to achieve more with less effort, or who prosper through means we would never use. A person who cuts corners gets promoted. Someone who lies and manipulates accumulates wealth. Meanwhile, our honest efforts seem to yield little. We feel bewildered. We ask: What is the point of being good? What is the point of sincere effort, if results seem so arbitrary?

This bewilderment is not new. It has troubled seekers for ages. Shankara, in the 8th century, addressed it directly in his short but potent work, the Bhaja Govindam. In the second verse, he writes:

मूढ जहीहि धनागम तृष्णां

कुरु सद्बुद्धिं मनसि वितृष्णाम् ।

यल्लभसे निज-कर्मोपात्तं

वित्तेन तेन विनोदय चित्तम् ॥

mūḍha jahīhi dhanāgama-tṛṣṇāṁ

kuru sad-buddhiṁ manasi vi-tṛṣṇām

yallabhase nija-karmopāttaṁ

vittaṁ tena vinodaya cittam

O fool, give up the thirst to acquire wealth. Cultivate in your mind thoughts that are free from desire. Whatever wealth comes to you based on your own past karma, with that let your mind be content.

The phrase nija-karmopāttam is central. What comes to us is shaped by our own karma, the vast web of actions, intentions, and consequences stretching across time, much of which we cannot see or remember. We perceive only a small fragment of the picture. We see our effort today and the result tomorrow, and when they do not match, we feel cheated. But the full equation includes far more than we can perceive. There are karmic seeds planted long ago, in this life and in lives before, that are only now sprouting. There are consequences of actions we have entirely forgotten. The ledger is far more complex than our small window of perception can reveal.

This is not fatalism. Adi Shankara is not saying that effort does not matter or that we should simply accept whatever comes. He is saying that our obsession with immediate results blinds us to the deeper workings of karma & dharma. We cannot control outcomes. We can only control the quality of our action and the purity of our intention. When we act with sad-buddhi, right understanding, and vi-tṛṣṇā, freedom from craving, we step off the wheel of anxiety. We do what is ours to do, fully and well, and then we release our grip on the results.

Shri Krishna teaches the same truth when he speaks of yoga as samatva, evenness:

योगस्थ: कुरु कर्माणि सङ्गं त्यक्त्वा धनञ्जय |

सिद्ध्यसिद्ध्यो: समो भूत्वा समत्वं योग उच्यते || 2.48||

yoga-sthaḥ kuru karmāṇi saṅgaṁ tyaktvā dhanañjaya

siddhy-asiddhyoḥ samo bhūtvā samatvaṁ yoga uchyate

Perform your duty steadfastly in yoga, O Arjuna, abandoning attachment to success and failure. Such evenness of mind is called yoga.

The one established in yoga acts with full attention and dedication, but is not destroyed by failure or inflated by success. Both are received with equanimity. The action itself becomes a form of practice, a way of being present, rather than a transaction with the future.

Swami Ranganathananda, in his commentary on the Gita, calls this the “democratization of spirituality.” In older frameworks, spiritual life often meant withdrawal from the world, retreat to forests and caves, renunciation of all activity. Shri Krishna opens another door. He says that action itself, when performed with the right understanding, becomes a path to liberation. The householder, the worker, the teacher, the doctor, the plumber…., all can walk this path. We do not need to abandon our responsibilities. We need to transform our relationship to them.

Buddhi Yoga: The Discipline of Seeing Clearly

But how do we develop this evenness? How do we break the deep habit of craving and anxiety that has accumulated over a lifetime? Shri Krishna introduces buddhi yoga, the yoga of discernment.

In the framework of Vedantic psychology, buddhi is the faculty of discernment, the capacity to distinguish what is real from what is unreal, what is permanent from what is passing, what leads to freedom from what leads to bondage. It is the aspect of mind that can step back and see clearly, rather than being swept along by reaction.

Without developed buddhi, we are at the mercy of the senses. The indriyas perceive their objects, form, sound, taste, touch, smell, and reactions arise automatically. We are drawn toward what seems pleasant and pushed away from what seems unpleasant. Rāga and dveṣa, attraction and aversion, run the show. We do not choose our responses. They happen to us.

Sthita Prajna: The One Whose Wisdom Is Steady

Near the end of the chapter, Arjuna asks a practical question. He wants to know what the sthita-prajña looks like, the one whose prajñā, wisdom, is sthita, firmly established.

Arjuna is asking for a map. He wants to recognize the destination so that he can direct himself toward that destination. This is wise. If we do not know where we are going, how will we know if we are moving in the right direction?

Shri Krishna’s answer is one of the most complete psychological descriptions in any spiritual literature. He describes the sthita-prajña from multiple angles: what such a person has released, how such a person relates to pleasure and pain, how such a person functions in the world.

The essence is this: the sthita-prajña is no longer driven by compulsive kāma, craving.

When one completely gives up all desires that arise in the mind, and is content in the Self by the Self alone, then one is called a person of steady wisdom.

This does not mean becoming inert or joyless. It means that happiness is no longer dependent on external conditions. The waves of life continue, but they do not drown the boat.

Shri Krishna also gives the famous image of the tortoise:

यदा संहरते चायं कूर्मोऽङ्गानीव सर्वश: |

इन्द्रियाणीन्द्रियार्थेभ्यस्तस्य प्रज्ञा प्रतिष्ठिता || 58||

yadā sanharate chāyaṁ kūrmo ’ṅgānīva sarvaśhaḥ

indriyāṇīndriyārthebhyas tasya prajñā pratiṣhṭhitā

When one withdraws their senses completely from sense objects, like a tortoise withdraws its limbs, then their wisdom is firmly established.

This is not a permanent withdrawal from life. It is the capacity to withdraw at will, to not be dragged. The sthita-prajña is not compelled by the senses. The senses serve the Self; they do not command it.

But Shri Krishna goes even deeper. He notes that even when we withdraw from objects externally, the rasa, the taste, the subtle craving for them, can remain.

This is an important teaching. Suppression is not freedom. We can force ourselves to abstain from objects, but if the craving remains, we are still bound. We are simply a prisoner who is temporarily locked away from temptation. True freedom comes when the craving itself dissolves.

And how does it dissolve? It dissolves when something higher is tasted. Paraṁ dṛṣṭvā, “having seen the Supreme.” When the heart experiences a deeper fulfillment, when awareness touches its own source, the old attractions lose their power. They are not suppressed through effort. They simply become uninteresting. A child obsessed with toys naturally loses interest in them upon growing up. Not through suppression, but through maturation. Similarly, when we mature spiritually, when we taste the ānanda that is our true nature, the lesser pleasures of sense objects fade on their own.

Brahmi Sthiti: The Final Vision

The chapter ends with one of the most exalted declarations in the Bhagacad Gita. Shri Krishna speaks of brāhmī sthiti, being established in Brahman, the ultimate reality:

एषा ब्राह्मी स्थिति: पार्थ नैनां प्राप्य विमुह्यति |

स्थित्वास्यामन्तकालेऽपि ब्रह्मनिर्वाणमृच्छति || 72||

eṣhā brāhmī sthitiḥ pārtha naināṁ prāpya vimuhyati

sthitvāsyām anta-kāle ’pi brahma-nirvāṇam ṛichchhati

O Partha, such is the state of a sthitaprajna that having attained it, one is never again deluded. Becoming established in this state, even at the hour of death, one is liberated from the cycle of life and death and reaches the Supreme Abode of God.

This is not a posthumous reward, a prize given after death in some other realm. It is a living condition, attainable here, in this life, in this very body. And Shri Krishna makes clear that it is accessible to the very end. Even if one attains this establishment only at the final moment, the result is the same: brahma-nirvāṇa, complete liberation.

Liberation, mokṣa, is presented not as a distant goal but as a practical possibility through the maturing of our consciousness. It is the natural flowering of ātma-jñāna, self-knowledge, and karma yoga, action without attachment, and buddhi yoga, the discipline of clear seeing. These are not separate paths but interwoven strands of a single rope that pulls us out of the well of saṁsāra.

Standing at the Doorway

When we reach the end of Chapter 2, we are not simply closing a lesson. We are standing at a doorway.

Shri Krishna has taken Arjuna from complete collapse to the first glimpse of inner freedom. He has shown that the battle is not only outside, on the field of Kurukshetra. The deeper battle is within, between deha buddhi and ātma buddhi, between craving and clarity, between restlessness and steadiness.

And yet, Arjuna has a doubt and a question is forming in his mind. This is the doubt and question that opens Chapter 3.

And it is a valid doubt. Shri Krishna has spoken of two things that seem, on the surface, to point in different directions: the path of knowledge and the path of action. Arjuna wants clarity. Which path leads to the highest good?

Verses 3.1 and 3.2

अर्जुन उवाच |

ज्यायसी चेत्कर्मणस्ते मता बुद्धिर्जनार्दन |

तत्किं कर्मणि घोरे मां नियोजयसि केशव || 3.1||

arjuna uvācha

jyāyasī chet karmaṇas te matā buddhir janārdana

tat kiṁ karmaṇi ghore māṁ niyojayasi keśhava

jyāyasī (ज्यायसी) – better; cet (चेत्) – if; karmaṇas (कर्मणस्) – than fruitive action; te (ते) – your; matā (मता) – opinion; buddhiḥ (बुद्धिः) – intellect; janārdana (जनार्दन) – O maintainer of all living entities; tat (तत्) – then; kiṁ (किं) – why; karmaṇi (कर्मणि) – in action; ghore (घोरे) – terrible; mām (माम्) – me; niyojayasi (नियोजयसि) – do You engage; keśava (केशव) – O Keshava.

व्यामिश्रेणेव वाक्येन बुद्धिं मोहयसीव मे |

तदेकं वद निश्चित्य येन श्रेयोऽहमाप्नुयाम् || 3.2||

vyāmiśhreṇeva vākyena buddhiṁ mohayasīva me

tad ekaṁ vada niśhchitya yena śhreyo ’ham āpnuyām

vyāmiśreṇa (व्यामिश्रेण) – with equivocal; iva (इव) – as if; vākyena (वाक्येन) – with words; buddhiṁ (बुद्धिं) – intellect; mohayasī (मोहयसी) – You are bewildering; me (मे) – my; tad (तत्) – that; ekam (एकम्) – one; vada (वद) – please tell; niścitya (निश्चित्य) – conclusively; yena (येन) – by which; śreyaḥ (श्रेयः) – the ultimate good; aham (अहम्) – I; āpnuyām (आप्नुयाम्) – may achieve.

Arjuna said: O Janardana, if You consider knowledge superior to action, then why do You ask me to wage this terrible war? My intellect is bewildered by Your contradictory advice. Please tell me decisively the one path by which I may attain the highest good.

This confusion is not a failure on Arjuna’s part. It is exactly the question that must be asked if the teaching is to go deeper. In Chapter 3, Shri Krishna will resolve this apparent tension by revealing that wisdom and action are not opposites.

The truly wise act, not out of compulsion or craving, but out of natural expression and for the welfare of the world. This is loka-saṅgraha, holding the world together through selfless action. And the one who acts without ego, without attachment, without craving for results, even while engaged in the most intense activity, remains inwardly free.

It is precisely because chapter 2 imparts such profound knowledge that chapter 3 must begin with a question. This kind of introspection is psychologically honest and spiritually necessary. Shri Krishna has exalted jñāna, the path of knowledge, with such clarity, and he has praised the stillness of the sthita-prajña with such authority, that Arjuna now feels a tension between what appears to be two paths.

On one side stands Sāṅkhya in the Gita’s sense, the discriminative vision that separates the eternal from the transient, the Ātman from the deha. This side of the teaching appears to point toward inner withdrawal, renunciation, and the quietude of realization. On the other side, Shri Krishna repeatedly urges Arjuna toward karma, toward action, toward fighting, insisting that retreat into inaction is not true spirituality.

Arjuna’s confusion is the very confusion that arises when a sincere seeker tries to integrate transcendental wisdom into their own lives. If the highest state is inner freedom and detachment, if wisdom is superior to restless activity, then why should Arjuna engage in ghora karma, dreadful work, especially the violence of war? Why should he be pushed toward action when the ideal of freedom seems to align with renunciation? Arjuna asks for decisive clarity, what is the right direction that leads to śreyas, the highest good.

There is also a personal undercurrent here that makes the Gita profoundly human. Arjuna had already leaned toward withdrawal before Shri Krishna spoke. He wished to renounce the battlefield, not necessarily out of spiritual realization, but out of emotional exhaustion, fear of consequence, and the unbearable weight of grief. When Shri Krishna spoke of inner peace, withdrawal from sense objects, and freedom from desire, a part of Arjuna likely heard validation of his own reluctance. That is human tendency. We always hear what we like to hear, not necessarily what is actually being said.

Yet Shri Krishna skillfully clarifies Arjuna’s apparent confusion. He refuses to allow Arjuna to confuse weakness with vairāgya, true dispassion. This refusal creates friction, but it is a sacred friction. It forces the student to mature, to rise beyond self-justification, and to seek a deeper integration where action is not bondage, and renunciation is not escape.

Chapter 2 is primarily Shri Krishna’s teaching, delivered to a student who is still recovering from emotional collapse. By Chapter 3, Arjuna has regained enough steadiness to question, to examine, and to demand coherence. The teacher-student relationship deepens into the classical Vedantic mode, where inquiry is not rebellion, it is the very instrument by which clarity is born. The central tension of spiritual life is now placed on the table without compromise.

- How do jñāna and karma relate?

- How does inner realization coexist with outer duty?

- How can one be established in the Self and still move through the world of obligations?

Introduction to Chapter 3: Karma Yoga

Chapter 3 is known as Karma Yoga. Chapter 2 gives the vision, the metaphysical truth of the Ātman, and the ideal, the sthita-prajña established in brāhmī sthiti. Chapter 3 gives the method by which that vision becomes lived reality in the midst of worldly responsibility.

For the sincere seeker standing in the world, surrounded by duties, relationships, and the ceaseless demands of living, a pressing question remains. How does one move from here to there? The vision of the Ātman may be intellectually grasped, but the pull of desire, the weight of obligation, and the confusion of daily choices do not simply dissolve because a truth has been heard.

Chapter 3 addresses this confusion with remarkable skill. Its teaching matters because it speaks directly to the vast majority of seekers, those who cannot and should not abandon their responsibilities. Mokṣa is not achieved by escaping life. It is achieved by transforming one’s inner relationship with life.

There is wisdom in the Gītā’s sequencing. By placing this chapter immediately after the philosophical heights of Chapter 2, the teaching ensures that its vision does not remain abstract or just theoretical. Before going on to subtler teachings of devotion and deeper contemplations of knowledge, this chapter establishes the essential ground of daily living. Action cannot be avoided. The only real question is whether action will become bondage or liberation.

Chapter 3 answers with clarity that is both uncompromising and compassionate. Action becomes bondage when craving rules it. Action becomes liberation when it is transformed into offering, discipline, and inner freedom. In that transformation, Kurukṣetra becomes every seeker’s classroom, and life itself becomes yoga.

Open-Floor Discussion Questions

These questions are designed to be “safe” yet provocative. They don’t require Sanskrit knowledge to answer, but the answers will reveal if the students understood the philosophy.

- The “Gandiva” Moment “In the text, Arjuna’s bow slips from his hand because his anxiety became physical. We all have a physical ‘tell’ when we are overwhelmed by shoka (grief) or stress. For some, it is a tight chest; for others, it is a migraine or shaky hands. What is your physical signal that you have fallen into deha-buddhi? How can you use that physical symptom as an alarm bell to wake yourself up?”

- The “If I Don’t Care, Will I Fail?” Debate “Krishna teaches nishkama karma, acting without desire for the fruit. A common fear is that if we stop craving the result (the ‘A’ grade, the promotion, the money), we will lose our motivation and become lazy. Do you agree or disagree? Can you be intensely ambitious about the process while being indifferent to the outcome? Has anyone here ever tried that?”

- The Modern Tortoise “We talked about the sthita-prajna withdrawing their senses like a tortoise. In 2024, our ‘sense objects’ are mostly digital. Be honest, what is the one app, website, or habit that drags your mind away against your will? If you had to apply the ‘tortoise technique’ to that specific thing for 24 hours, what exactly would you have to do? Would it be painful?”

- The Cost of Anger “Krishna warns that anger leads to smriti-bhramsha—loss of memory. This doesn’t mean amnesia. It means forgetting who you are and what you value in the heat of the moment. Can you share a time when anger made you say something you immediately regretted? In that moment, what ‘knowledge’ did you lose access to? How long did it take for your buddhi (intelligence) to come back online?”

References

Swami Ranganathananda, Universal Message of the Bhagavad Gita, An Exposition of the Gita in the Light of Modern Thought and Modern Needs.

Swami Chinmayananda, The Holy Geeta, Central Chinmaya Mission Trust.

Swami Gambhirananda, Bhagavad Gita, With the Commentary of Shankaracharya.

Swami Mukundananda, Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God.

kṛṣṇadaasa

Servant of Krishna